Unexpected side effect: How common medications pave the way for pathogens

Many non-antibiotics weaken the intestine's natural protective function, making it easier for disease-causing bacteria to colonize it

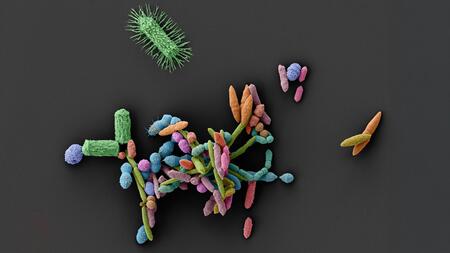

Scanning electron microscope image of an intestinal bacterial community (1:1,000,000). These microorganisms form an ecosystem through their interactions that is essential for human health. Medications can severely disrupt this fragile balance by eliminating beneficial bacteria and promoting the growth of harmful species.

The human gut is home to a dense network of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome, which actively contributes to health. These microorganisms aid digestion, train the immune system, and protect against dangerous intruders. This protection can be disrupted by antibiotics, which are used in therapy to inhibit the growth of disease-causing bacteria. A new study shows that many other drugs can also alter the microbiome. This makes it easier for pathogens to grow in the gut and cause infections. The study was published in the journal Nature and was led by Professor Lisa Maier from the Interfaculty Institute of Microbiology and Infection Medicine (IMIT) and the Cluster of Excellence "Control of Microorganisms to Combat Infections" (CMFI) at the University of Tübingen. At the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) Maier conducts research at the Center for Gastrointestinal Microbiome Research (CEGIMIR) and coordinates the Bridging Topic "Microbiome".

The researchers investigated 53 common non-antibiotics, including allergy medications, antidepressants, and hormone preparations. Their effects were tested in the laboratory in synthetic and human stool-derived intestinal communities. The result: around one-third of these active substances promoted the growth of Salmonella, bacteria that can cause severe diarrhea. Lisa Maier, the senior author of the study, says: "This extent was completely unexpected. Many of these non-antibiotic drugs inhibit beneficial gut bacteria, while disease-causing germs such as Salmonella Typhimurium are unaffected. This creates an imbalance in the microbiome that gives pathogens an advantage."

Pathogens remain, protective bacteria disappear

The researchers observed a similar effect in mice: certain drugs led to increased Salmonella growth. This resulted in severe salmonellosis, characterized by a rapid onset of the disease and severe inflammation. The mechanism of action is complex, report the study's lead authors, Dr. Anne Grießhammer and Dr. Jacobo de la Cuesta from Lisa Maier's research group: The drugs reduced the total biomass of the gut flora, disrupted biodiversity, or eliminated bacteria that normally compete with pathogens for nutrients. This removes the natural competitors of disease-causing germs, such as Salmonella, permitting uncontrolled proliferation.

"Our results show that, when taking medication, one must consider not only the desired therapeutic effect, but also its influence on the microbiome," says Grießhammer. "Taking medication is often unavoidable. However, even active ingredients with supposedly few side effects can cause the microbial protective wall in the intestine to collapse." Maier adds: "It is well known that antibiotics can disrupt the intestinal microbiome. Now we have strong evidence that many other drugs also damage this natural protective barrier. This can be dangerous for weakened or elderly people."

Call for reassessment of drug effects

The researchers recommend that the effect of drugs on the microbiome should be systematically investigated during development— especially for drug classes such as antihistamines, antipsychotics, or selective estrogen receptor modulators, and when multiple drugs are combined. Lisa Maier's team has developed a new high-throughput method that can be used to quickly and reliably test how drugs affect the resilience of the microbiome under standard conditions. This large-scale screening is intended to help identify risks early on and adapt therapies. These findings require a rethink in drug research. In the future, drugs should be evaluated not only pharmacologically, but also microbiologically. "Disturbing the microbiome opens the door to pathogens. It is an integral part of our health and must be considered as such in medicine," Maier emphasizes.

Source: Press release of the University of Tübingen (German only)