With Passion and Humour

It happened so incredibly fast that she can still hardly believe it. Until September last year, Marylyn Addo and her family lived in Boston, where the physician and infectologist had successfully researched AIDS viruses and the reactions of our immune system for 15 years. Now she is sitting in a brand new office at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) as the first DZIF professor, and will be working on the topic “Immunity and pathogenesis of newly emerging viral infections” in the coming years.

“It is actually a stroke of luck that I got this DZIF position at this particular point in time,” says Marylyn Addo happily. And that is in many respects. At almost the same time, her husband, also a researcher in the field of infectiology, received an offer from the Heinrich-Pette-Institute which is in close proximity to the UKE. So after 15 years of living abroad, the family moved back to Germany and their parents are now virtually within reach in the Cologne/Bonn area. The growing importance of infection research also played an important role in this, which Addo thinks is just a matter of course. “When I moved to London after my PhD and subsequently to the USA, there were few resources available in Germany for infection research,” remembers Addo.

She grew up near Bonn where she also completed her medical studies. After this, the young researcher quickly moved abroad. “Of course, it is also thanks to my roots that I think and live more globally.” Marylyn Addo’s father is from Ghana and, besides her exotic name and looks, she inherited her affinity to medicine from him together with a great interest for Africa and its problems. She found her research topic, the HI virus, early on during a study visit in Strasbourg where she worked with the AIDS pathogen for the first time. It has not let go of her in her career path since.

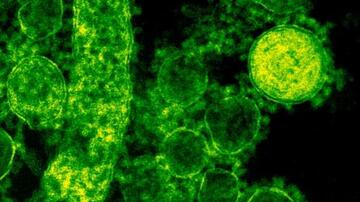

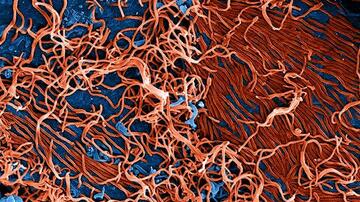

HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS, was the first newly emerging pathogen to trigger global fear and dread in a long time. Its discovery and spread about 30 years ago was a new challenge for infection researchers. HIV was followed by SARS, EHEC and swine flu, and there is no end in sight for these abruptly emerging aggressive pathogens. On the contrary: in an era of global mobility, viruses and bacteria also know no borders. The pathogens responsible for new infections are frequently viruses transmitted from wild animals to humans which then mutate into aggressive forms.

“We have gained substantial ground regarding AIDS treatment,” says Addo. Her research has contributed substantially to this success. After spending one year in London, where she acquired a Masters in Applied Molecular Biology of Infectious Diseases and a Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Addo moved to the USA and worked at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. There she initially researched HIV-1 infections and the cytotoxic T lymphocyte reaction in the human immune system. These cells, also known as killer T cells, are specialised to defend against virus and cancer cells. Her focus of attention was on the group of so-called HIV controllers: People who do not develop AIDS despite being infected with HIV. Finding out the reasons for this would help to develop effective vaccines or improved drugs. Addo created national and international cohorts of HIV controllers, which today comprise over 1500 individuals and form the basis of many research results.

“We have achieved a series of interesting results with this cohort,” says Addo. For example, with her results she could show that the quality of immune response and T cell maturation are different in HIV controllers and people who develop AIDS. What she did not specifically highlight was that one of her papers on immune response was among the top 5 in AIDS research. In 1999, her research activities brought her to Harvard Medical School in Boston, and she has been Assistant Professor at the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard since 2010. This institute coordinates HIV/AIDS research on a global scale.

Despite all her laboratory work, Marylyn Addo has not lost sight of the patient, especially not of the people in South Africa who have benefited least from the drugs. For this reason, Addo also regularly researches on-site in Durban, South Africa, where she is involved with clinical studies, research and training. She was recently also awarded honorary professorship at the KwaZulu-Natal University.

International research, commitments in South Africa, trips to congresses and conferences, and besides this a family with two children. How does she manage all this? Marylyn Addo smiles when asked about her 11-year-old son and her 4-year-old daughter. “In the first years, you have to put a lot of money into good child care, and you need support from both your husband and grandparents.” She has always been able to rely on them in emergencies, despite the distance between Bonn and Boston. The grandmothers have occasionally even packed their bags to come to South Africa and look after the children. Children and career – Marylyn Addo knows the balancing act women often have to go through to not fall by the wayside. So in the past few years, besides all her work, she has also been active in a committee that promotes women in science.

And how will her research continue? “The DZIF professorship offers a lot of scope for new projects. I will continue focusing on viral immunology and vaccine development,” Addo explains. With this she fits perfectly into the group of DZIF scientists dedicated to the topic of “Newly emerging infectious diseases”. One focus will be to develop methods with which new pathogens can be diagnosed quickly and reliably. At the same time, the DZIF researchers work on designing strategies for developing novel drugs and vaccines. The UKE in Hamburg works in close collaboration with the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine.

Addo is certain, “The results from HIV research will also help us gain ground with other viruses.” An important goal will be to be better prepared for new outbreaks and to produce vaccines quickly. Addo also believes that professionals should be better prepared for communicating with each other and the public. In the acute event of an outbreak, social networks like Facebook and Twitter could also be used, the young professor thinks. In spring she will presumably be working clinically again, “An important prerequisite if you also want to supervise patient studies later on.”

Boston – Hamburg: A big step and the first 100 days are not yet over. But Marylyn Addo accepts the challenges of a new beginning with humour. “That’s always helped me,” she admits, “I am, after all, a cheerful Rhinish soul”.