Dangerous and “jumping” mcr-1 resistance gene

The mcr-1 gene makes gut bacteria insensitive to the last-resort antibiotic colistin. Especially in hospitals, colistin is used as a last treatment option for infections with dreaded multidrug-resistant pathogens. At the beginning of this year, bacteria carrying this resistance gene were found in Germany, and have recently also been confirmed in a patient in the USA. Scientists from the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) and the Justus Liebig University of Gießen (JLU) have investigated the transferability of this gene. Amongst other things, they discovered that the mcr-1 gene not only exists on mobile plasmids, but be integrated into chromosomes as well. Consequently, it can be reliably passed on to next generations.

Recently, the “superbug” E. coli carrying the mcr-1 resistance gene, amongst others, was found in a patient suffering from urinary tract infection. This gene has long been widespread in livestock, and its emergence in humans has given rise to concern. “Some Gram-negative pathogens, such as certain Escherichia coli strains have become resistant to newer broad band antibiotics. Often, only colistin, the last-resort antibiotic, can help,” explains Dr Linda Falgenhauer, DZIF scientist at the Justus Liebig University of Gießen and first author of the current study. “If this drug now also fails, treatment will become even more challenging.”

How high is the danger of a further spread of colistin resistance? Up to now, it has been known that mcr-1 is transferred by plasmids, mobile genetic elements. Due to this transferability, the gene is now found in many different types of bacteria. Evidently, it is able to “jump” into different plasmids and consequently cross species barriers. Now, the scientists are concerned that plasmid into chromosome “jumping” could also occur.

“If the gene jumps into bacterial chromosomes, the situation will get particularly dangerous,” explains Linda Falgenhauer, “because then, colistin resistance would reliably be passed on to the next generations.” If such chromosomal resistance emerges in bacteria circulating between humans and animals, for example through food consumption, these resistant pathogens would have a reservoir over many generations.

Resistance is inheritable

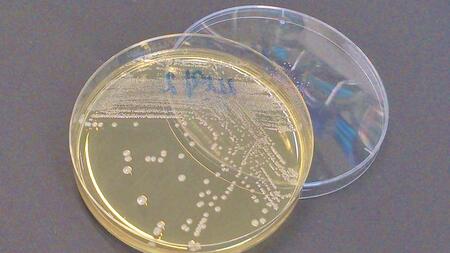

The Gießen researchers have found out that precisely this has already happened. In their current publication, they describe a multidrug-resistant strain of E. coli, sequence type ST410, which has existed in humans, animals, the environment and food in Germany for years. The scientists discovered that, alongside the ESBL gene which causes resistance to extended spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics, this strain also carries the mcr-1 gene in its chromosome, which causes colistin resistance. Both genes can be passed on over generations, hence making these bacteria a reservoir for the antibiotic resistance.

The discovery of the E. coli ST410 strain suggests that bacteria coding for mcr-1 which circulate in humans and animals already exist, and can hence be transferred much more easily than has been previously described.

In the current project, DZIF scientists have been working together with project partners from the research association RESET which is dedicated to researching antibiotic resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. “The research team unites expertise from scientific institutions and public health services. This interdisciplinary collaboration uses the One Health concept which takes into account the systematic connections between humans, animals, the environment and health to fight antibiotic resistance,” says Prof Trinad Chakraborty, Director of the Institute of Medical Microbiology at the JLU Gießen and Coordinator of the DZIF partner site Gießen-Marburg-Langen.